2024-4-12 11:24 /

由手,相连结——

河野史代漫画《谢谢你,在世界的角落找到我》中的美学物质性

原作者:杰奎琳·伯恩特(Jaqueline Berndt)

文章原名:Conjoined by Hand: Aesthetic Materiality in Kouno Fumiyo’s Manga In This Corner of the World

翻译:FISHERMAN

原文链接(Project MUSE)

譯者按:

-「飛走了。」

-「是非正義,從這個國家飛走了。」

-「這是要我們向暴力屈服嗎?」

-「......唉。」

-「意思是我們得向暴力低頭嗎?」

-「這就是這個國家的真面目?」

-「真希望我也能在發現真相前就死去...」

-「我不能同意我的女儿离开我的祖国,为了奔向祖国,我走了半辈子黑路......」

-「爸爸!我走,是跟着我爱的人走,我爱他,他也爱我;我知道您,我太知道您了,爸爸!您爱我们这个国家,苦苦地留恋这个国家......可这个国家爱您吗?!」

正文:

近年来,对日本动画和漫画所展开的内容驱动式、或表象式【译注1】的解读正逐渐受到中介式(mediatic)研究方法的挑战,然而,这些研究的重点大体上还是各类平台和体制(institution)的物质性,而不是那些在最开始便为作品本身实现了一定程度的中介化的,能指和人工制品(artifact)的物质性。河野史代的漫画《谢谢你,在世界的角落找到我》(この世界の片隅に,后文简称《角落》)为研究日本漫画的美学物质性(aesthetic materiality)提供了一个绝佳的案例,原因之一是:由片渊须直执导的同名动画电影(动画制作:株式会社MAPPA,2016年上映)[1] 对漫画原著进行了忠实的改编,二者相得益彰。这部电影,证实了约翰·基洛利(John Guillory)在其他语境下所提出的观点,即——「[再]中介化,使得中介本身变得可见。」[2] 因此,作者将在下文中用《角落》的动画改编衬托漫画原著,藉此突显河野的漫画究竟是如何运用一种基于绘制线条、纸媒印刷(print on paper),以及叙事-连载形式的媒介(中介)-特异的方式,将不同的物质性连结(conjoin)起来的。

本文从物质性的角度探究日本漫画的媒介性——这种视角并没有重申那种以现代主义式的“作者身份”(authorship)和“自主艺术”(autonomous art)概念为蓝本的去语境化的形式主义,而是将形式自身视作一种美学可供性(affordance)。首先,考虑到媒介特异性(的制约),作者将试着尽可能在不受其影响的前提下对《角落》的故事情节进行总结,以便在之后展示:对美学物质性的关注可能会引导读者所看见的,或更确切的说,引导读者所成为的那个角色——即,一位成熟的参与者。其次,作者主要关注「手-绘」(hand-drawing),以及各种绘制线条的优先性;作者将要指出的是,在河野的漫画中,美学物质性既不会促成作者身份的确立(由艺术家手部的痕迹显现),也不会使漫画媒介成为一种艺术形式(由作为文本自身属性的、现代主义式的自反性所显现),而是将助长一种涉及艺术家、虚构角色和读者——TA们在过去和当下之间建立起连结——的共通性,亦或,分布式的能动性。然后,作者将转向讨论更常与物质性联系在一起的事物,即出版媒介的物理特性(physicality)。与其分析纸张质量(这指的是日版书刊所采用的粗糙泛黄的印刷纸,它难以在海外复制生产),作者优先考虑的是线条-绘制(linework)、字体设计(lettering)、画格分割(paneling),以及,漫画单章在连载杂志内部的物理定位。作者认为,这些方方面面是与漫画这一流派的传统(创作方式)息息相关的、非言语的表述,并且,作者将它们与早在《角落》标题中便已提及的「边缘性」(角落-边缘)主题关联了起来。总体而言之,作者希望证明:对日本漫画物质性广义上的关注(一种泛指...这包括对表征形式、中介化形式、分布形式、以及知觉形式的,非表象主义式的关注)能够实现面向通俗作品进行的,以及,能够承认通俗作品之包容性潜能的,批判性阅读方式。

在讨论过程中,作者将会一再提及《角落》和那些由全球畅销作品所代表的“中规中矩的”日本漫画之间的区别。河野史代漫画作品的特征在于,它不仅连结了角色和时代,而且,还同时连结了一种(布迪厄语境下的)「倾向/秉性」(disposition):这些作品在遵循日本漫画的传统(创作规范)的同时,亦改变了这种传统本身,藉此,开拓了一片介于大部分以特许经营为导向的商业作品、和充满作者表现力(authorial expression)的少数作品之间的,第三空间。虽然这种(创作)倾向适用于相当多的日本图像叙事——从手冢治虫 [火之鸟]、池田理代子 [凡尔赛玫瑰]、谷口治郎 [孤独的美食家]、浅野一二〇 [晚安,布布],再到今日町子 [COCOON)——但在欧洲或北美的漫画研究中,这种倾向仍然容易被边缘化,原因是,在这些研究对各种作品不容分说整齐划一的明确分类中,所谓的图像小说(graphic novel)被视为严肃的个人及政治叙事,而另一方面,所谓的漫画/日本漫画却被视作文化工业所生产出的、编码化的、连载的B级文学。[3] 在前述背景下,把类似河野史代作品那样的日本漫画称作“另类”(alternative)将会滋生错误的期望(对日本漫画及其研究而言),纵使它们比起其他作品而言,在和日本相关的本土和全球媒介景观内部,显得略微不同寻常了些。

手的物语

河野的图像叙事——《角落》于2007年1月至2009年1月间在双周刊《漫画ACTION》(漫画アクション)上连载。日版漫画分为上中下三卷,然而,英译版却把整整430页的漫画全部塞进了一本笨重的书里(总集篇Omnibus Collection),以适应一种与日本不同、较少依赖系列分卷的消费模式。[4] 为了与最初的杂志连载结构保持一致,漫画书以3幕无编号的序章打头,紧接着,则是总计44章的有编号章节(第1-44章),以及,最末的一篇“终章”;每个章节构成了一则相对独立的短篇故事,它们的篇幅通常为8页纸(有时,则是12、14或16页),而大部分章节会在结尾处抖上一个包袱。

《角落》所讲述的,是铃的故事:她是一位在广岛三角洲(距离后来的原爆中心大约3公里)长大成人的普通少女。故事情节在这位19岁的少女出嫁到广岛附近的吴市时(1944年2月)正式开始。在吴市,铃为大家做饭、打扫卫生,并照顾她生病的婆婆,而家里的男人们则在外务工——铃的丈夫周作是帝国海军军事法庭的一名小书记官、她的公公是大日本帝国当时最大的海军基地造船厂里的一名工程师。来到世界的这个角落的铃孤身一人,她经常受到嫂子黑村径子的责骂...在这一隅,她唯一的慰藉只有绘画。小时候,铃便在短篇漫画中将长兄描绘成“鬼哥哥”来缓解他的专横霸道(所带来的伤害)。在吴市,铃的绘画在帮助她应对陌生环境的同时,亦使她“免于”战争的影响【译注2】。1945年6月,铃在延时炸弹的爆炸中失去了外甥女晴美和她的右手。几个月后,她得知了父母的死讯和妹妹在广岛患上辐射病的噩耗。故事的最末,铃和周作在广岛收养了一位战争孤儿。

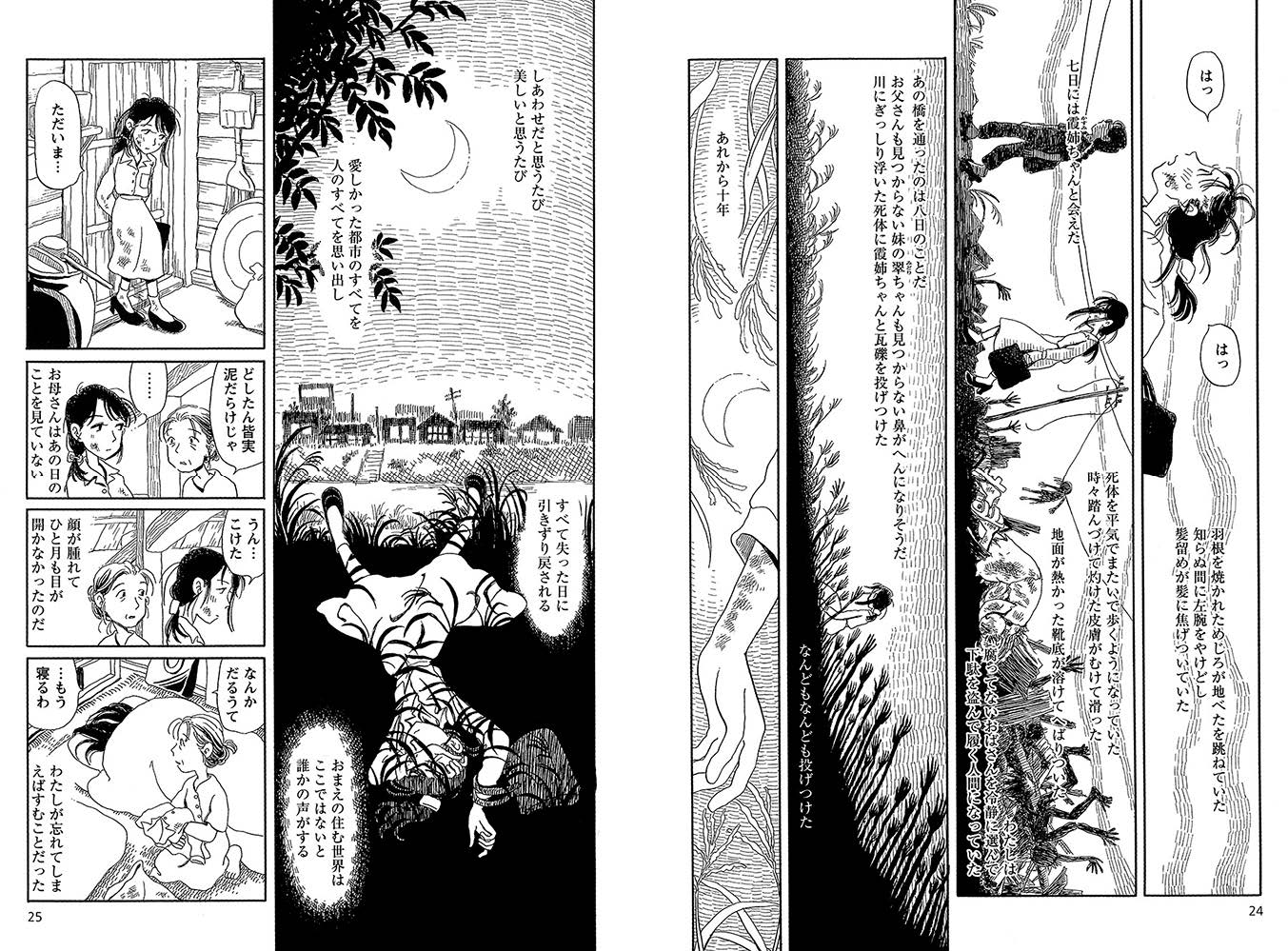

《角落》的标题对一本首次出版于广岛原爆二十周年祭的纪实文集进行了指涉。然而,山代巴编著的那本纪实文学强调的是1945年的“角落”(この世界の片隅で:“在这世界的角落”)和广岛[5],而河野在漫画标题中使用的,则是可以同时表示指向与所在的日语助词(この世界の片隅に:“进入/在这世界的角落”):这既表示了女主角搬到另一座城市的举动,也暗示着读者对战时-过去的关注/定位。2016年上映的改编动画激起了大众对河野叙事的广泛关注,并主要推动了对《角落》的两种解读方式:其一,是将它视作一则战争故事、其二,则是将它视为一部“以女性的坚忍为主题的时代剧”[6](日本自我受害者化的战后话语是在[自我]女性化的进程中运作的,而这两种解读都或多或少地受到了这种话语的支持/影响 [7])。不过,在影评人认为电影没能充分探讨战争责任的同时[8],河野本人却表示,她想用“在日本被自然化、被广泛认同的那个视角”以外的视角,来展现广岛。“不知为何,我不愿观看和描绘与原子弹有关的事物。我想,我并不喜欢将‘原子弹’和‘和平’直接联系起来的那种事实(真理)。好像原爆赐予了我们和平似的!”[9]

然而,战争并不是漫画或动画电影当中唯一的叙事驱力。尽管动画赋予了男性角色更多的空间,并且通过他们的职业拓展了(动画所描绘的)社会光谱,但女性依然处于核心地位——这包括铃、和她的对立角色径子(她曾是一位摩登少女,自由恋爱、结婚,但在丧偶后被迫将儿子交由公婆抚养,除此之外,她在吴市市中心的家也因为要搭建空袭防火带而被拆除)。第三种昭和历史背景下的女性,是铃在吴市迷路时所邂逅的游女白木兰(リン):她和吴市的【Red-light district】,一并消逝于1945年7月的空袭。2016年的动画电影将兰边缘化,并删减了周作在婚前与她之间的(恋爱)关系;在日本境外,这种处理方式有助于将电影作为一部讲述铃和周作逐渐萌芽的婚姻-爱情故事的作品来进行宣发。

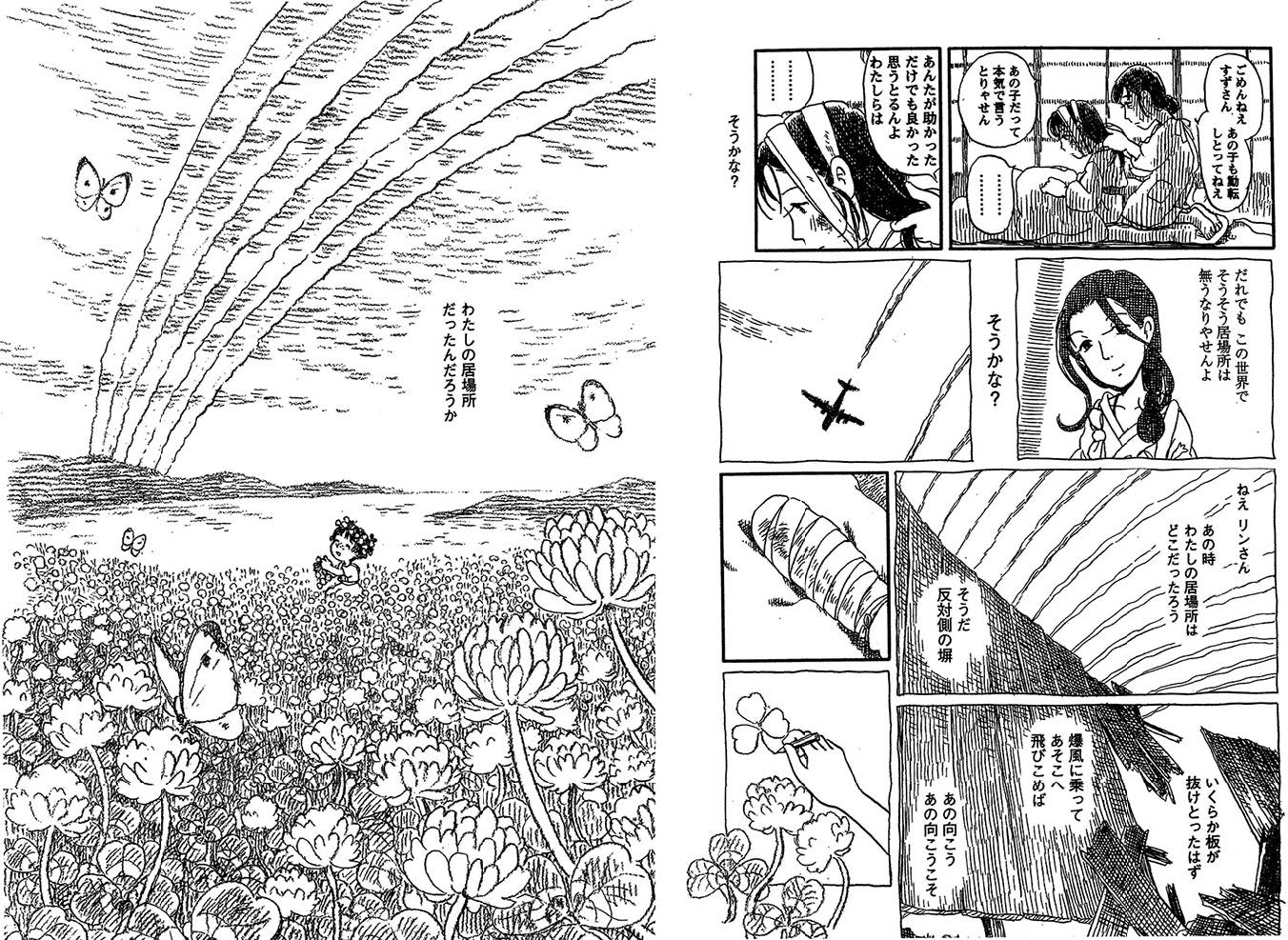

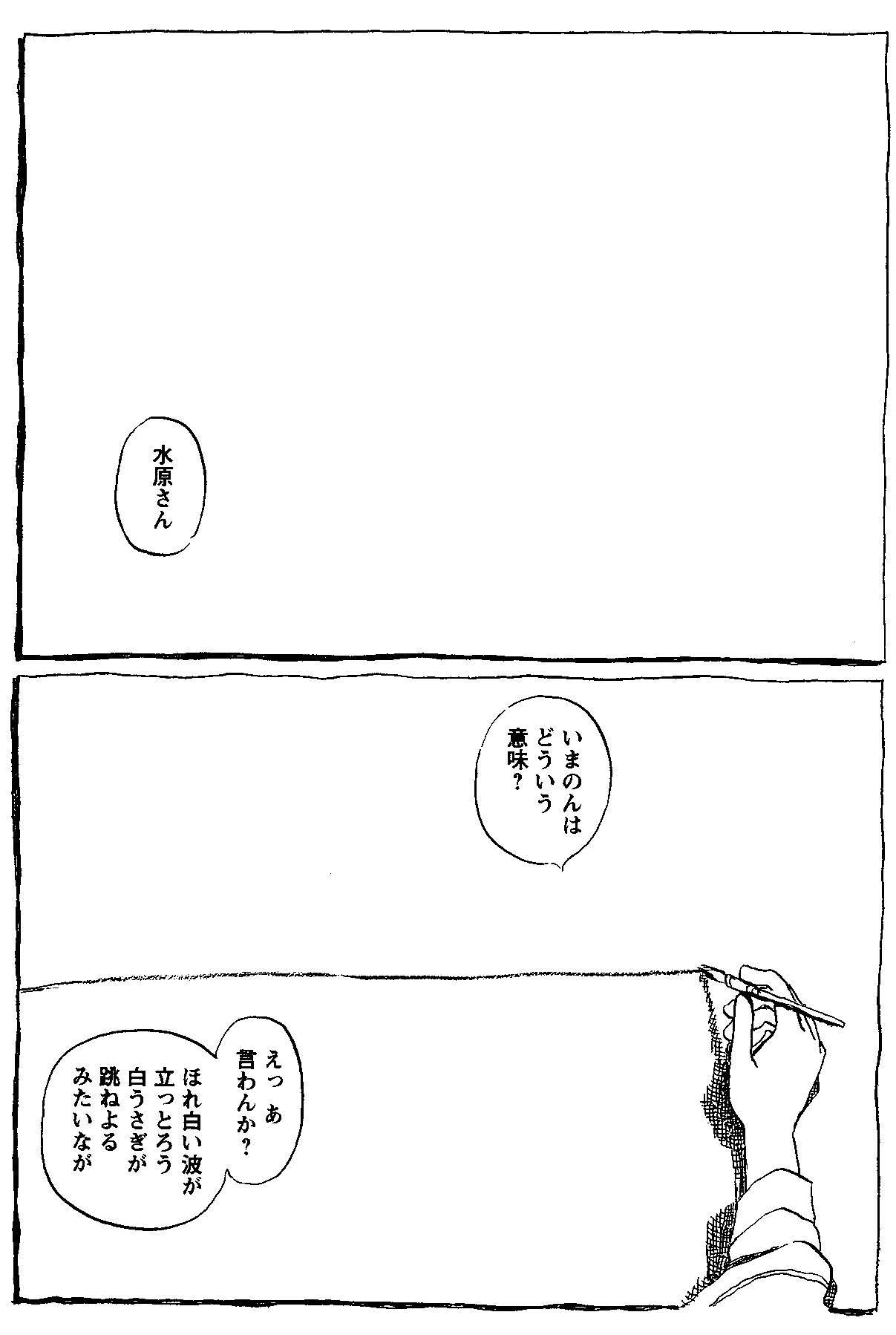

考虑到改编动画对原著漫画的再中介化,《角落》所描绘的似乎不止战争与爱情...它还描绘了一只绘画的手(a drawing hand)。細馬宏通教授出版了一本对《角落》漫画和动画进行过细致考据的文集,而他断言:动画电影完全将叙事视角从铃本人转移到了她的右手上。[10] 河野自己也承认(日版)漫画第三卷展现了这种转变,她在一次采访中说道,“...从这一刻起,便是手的物语了。”[11] 仿佛自一开始便在朝着视角的转移迈进一般,漫画中偶尔会出现这样的画格——它们都描绘了放置在空背景前方的一只手。这种设计从序章第三幕开始:在纸页左下角的画格(按照日本的阅读方向,这是读者在翻页前所看到的最后一个画格)中,出现了一只拿着(指向左侧的)铅笔头的手;十八页漫画(对于铃来说,则是五年)过后,相似设计的画格再次出现,只不过,现在这只手握着的是一双筷子,它指向左端,促使读者更进一步【译注3】。当延时炸弹在漫画第32章最后一页爆炸后(见图1),显然,铃不仅失去了她的外甥女,而且还失去了她那只用来绘画的手,不过,从这时开始,这只右手便开始有了自己的生命,首先是,作为一幅心理图像(mental image):铃的右臂残肢缠上了绷带,但是,这一画格正下方所对应的画格中,却出现了一只完好无损的右手,它勾画了一株三叶草,随后,这株植物长成了一片花园——有晴美在此玩耍的,天国的花园(见图2)。第39章中,在1945年8月15日的玉音放送结束后,铃跪在菜地里哭泣,此时,这只手从(天空/画格的)上方降下,安抚了铃的头部。在《角落》的最末,这只右手甚至发出了自己的“声音”:它拿起笔,开启了故事的终章,并在自己用画格与手写独白组成的书信体和铃对话之后,再次被实体化,随后,它被安置在一片自由空间【译注4】中。现在,这只右手自己握着画笔,为其余的页面水彩上色。

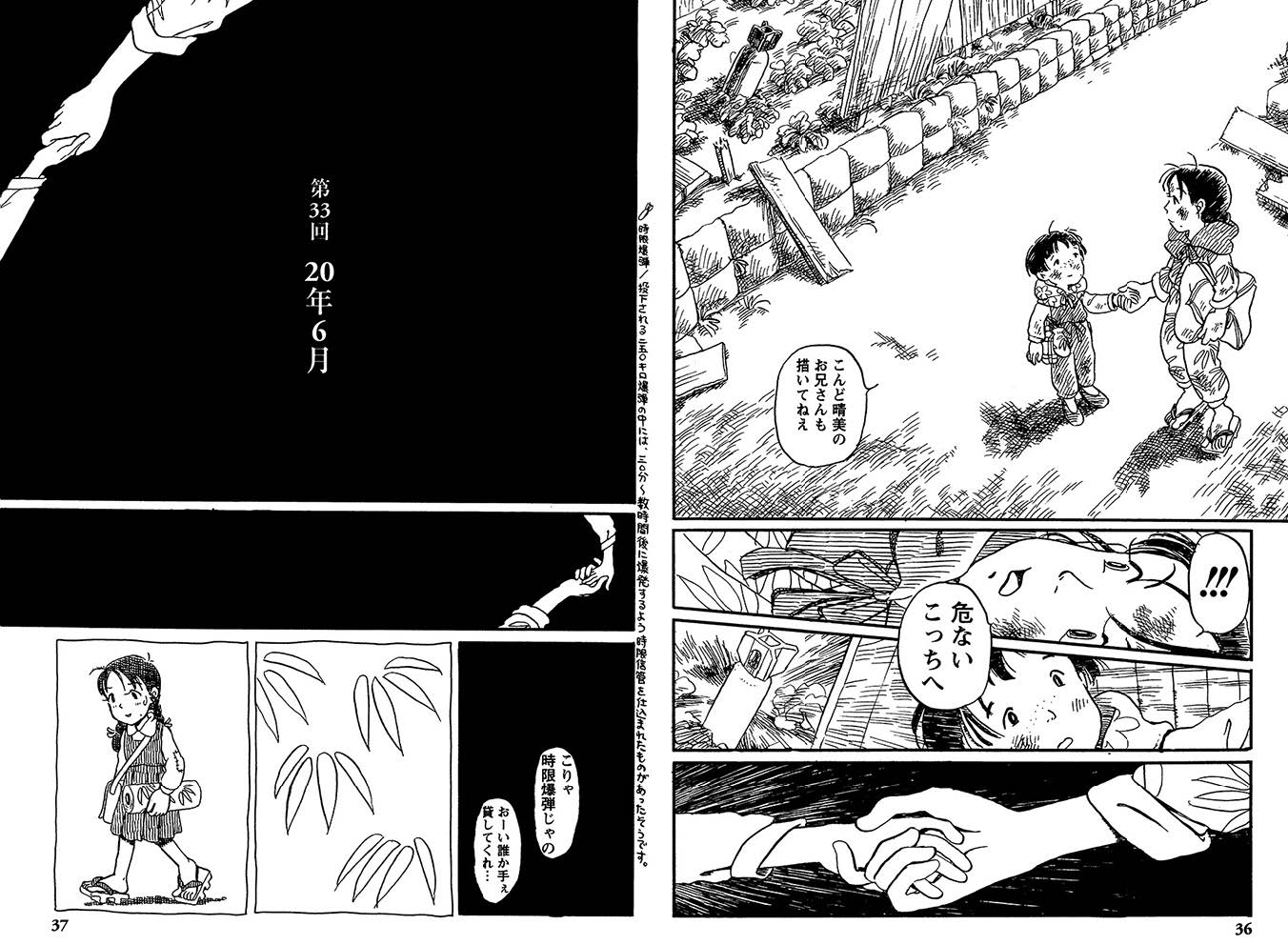

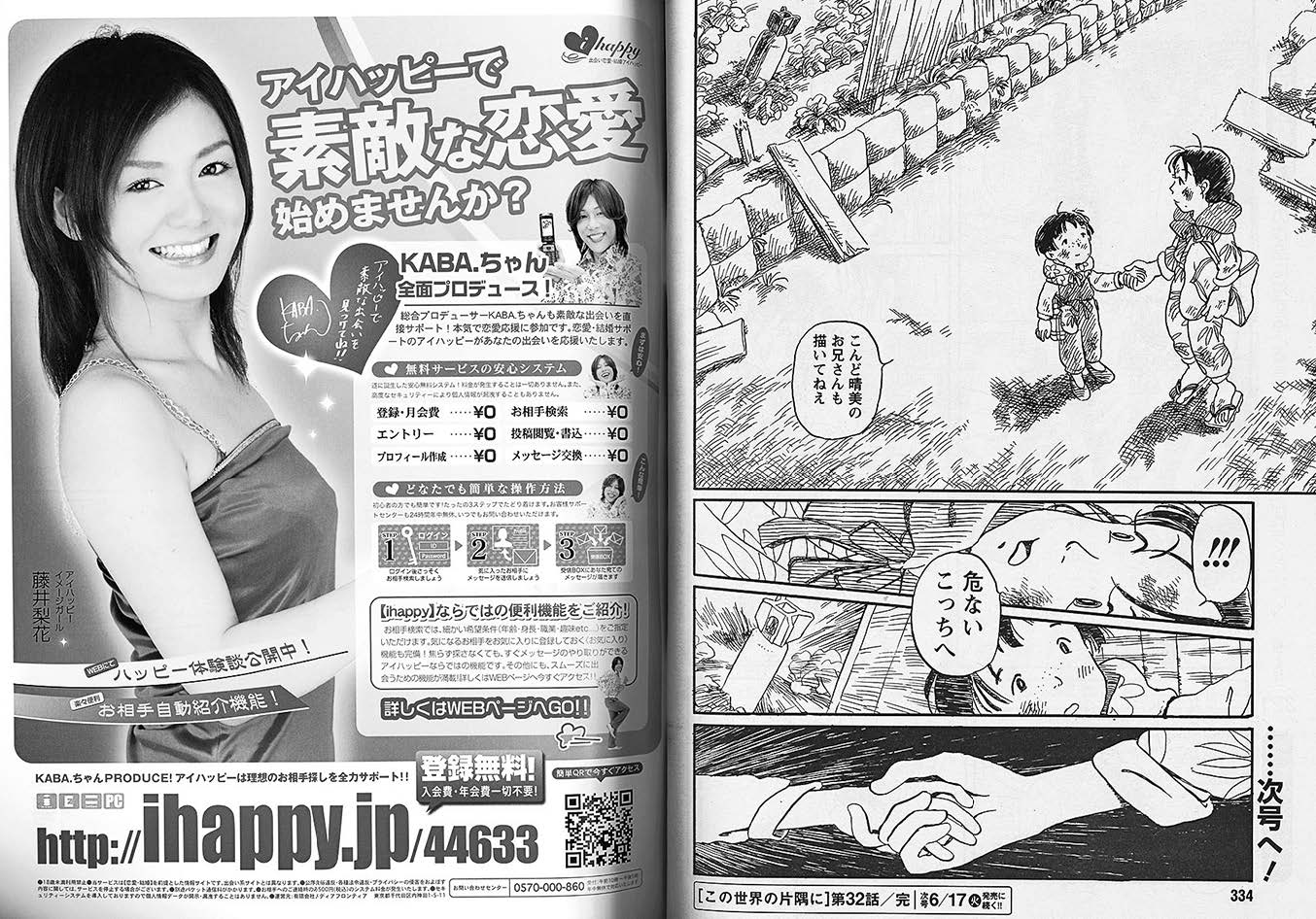

图1. 右半页:<第32章 - (昭和)20年6月>【译注5】;左半页:<第33章 - 20年6月 [指1945年]>。河野史代,《在这世界的角落 (下)》(この世界の片隅に (下)),东京:双叶社,2009年,页36-37. © 河野史代、双叶社,2009年

图2. 失却之手的复归;引用信息同上。

触感的参与

但是在河野的漫画中,「手」远远不只是一个吸引读者关注它所表征的事物的母题。在任何象徵主义的诠释之前,它所发挥的首先是实用功能,也就是,邀请读者进入故事世界。比起采用角色面部特写的常规日本漫画,《角落》选择让手的特写来承担这一重任。手的功能,早在序章第三幕中便已显现:铃的同学水原送了她一支铅笔,请她代自己完成绘画作业——对应跨页的右半部分用七个直尺描边的画框讲述了这段情节,而跨页左半部分所描绘的,则是两个几乎空空如也(除了右手和对话框)、并且在左边框和下边框处被涂上阴影的长方框(见图3)。

图3. 铃开始画画。河野史代,《在这世界的角落 (上)》(この世界の片隅に (上)),东京:双叶社,2008年,页45. © 河野史代、双叶社,2008年

位于上方的长方框中有一个不含指向性尖角的椭圆对话框,里面写着铃的对白;位于下方的长方框展示了铃正在朝右画下线稿的右手、和它左侧的两个对话框。然而,在这页漫画中,她那从画框底边处凸起的右前臂,亦是长方框的一部分。与动画电影不同的是,漫画这种媒介能够让铃的右手成为通往空白空间(empty space)的入口:这个空间,既是主角手中的画纸,亦是读者手中的漫画书页。接踵而来的重叠感(如前所述)在下一个跨页中愈加强烈,在那里,河野/铃笔下的画页/画纸边角仿佛要卷起来一般【译注6】。进而,读者以一种表象性与物质性兼有的方式,和主角连结在了一起。

在讨论作为纸质媒介的漫画(comic)的特异性以及它在数字时代的持续存留时,卡塔琳·欧尔班(Katalin Orbán)强调:漫画在很大程度上依赖着「与自身之物质基础永久结合在一起(在读者的体验中如是)的印刷文本。」[12] 欧尔班在引用阿洛伊斯·李格尔(Alois Riegl)时指出:「因此,物质性的感觉大体上是通过触觉关系建立起来的,在这种关系中,手与书本之间的接触以及触感视觉性(haptic visuality)相互影响着对方。」[13] 劳拉·U·马克斯(Laura U. Marks)以视频图像及其颗粒感为例论证触感视觉(haptic vision)[14],相比之下,在日本漫画这种被主要定义为“線画”[15]的漫画类型中,触感视觉是一种主要依赖绘制线条的,具身的观看形式。人类学家迈克尔·陶西格(Michael Taussig)认为,绘画是一种逼近(approximation)的手段:「绘制的线条之所以重要,并不在于它记录了什么,而更多在于它引导你看到了什么。」[16] 这句话受约翰·伯格(John Berger)对绘画的论述所启发,而实际上,伯格并未止步于观看:「每一次确认或否定都使你更加接近那个客体,直到最终,你仿佛已然置身其中:你所绘制的轮廓所标划的,不再是你所看到的事物的,而是你所成为之物的边缘。」[17] 伯格所理解的“绘画”大体上是一种自传式记录,而他则将这种观点应用于分析艺术家的成长历程;对比之下,在河野的漫画中,个人的绘画动作(act of drawing)超越了个人主义:它服务于角色之间的,以及艺术家、角色和读者之间的共通性;多义的「手」牵起了读者的手,并邀请他们抹去历史的距离——不是简单地回顾过去,而是实在地触摸过去。[18]

之前,河野曾尝试在六页长的短篇彩漫《守旧的女人》(古い女,2006年)[19]中渲染过如上所述的这种亲近感。这篇作品的主角同样是一位看似默默服从于日本现代父权制的年轻女性,她和铃一样是一位业余艺术家,只不过这次,她并不是在空白的画纸上,而是在各种传单背面的空白处画画。为了模拟这种介质,漫画画格所在的页面上印有浅淡的镜像图案——仿佛是从传单背面迎光透视所折射出来的那样。尽管这种效果在初次阅读时并不一定会引起读者的注意,但在仔细审视之下,它或许用一种讽刺的方式,削弱了对父权制与民族主义的口头肯定。这部作品和她的其他作品一样:河野冒着在政治(立场)上保持模糊的风险,呼吁读者成熟地介入作品承载的议题。

与水彩上色的短漫《守旧的女人》相比,《角落》这部黑白漫画完全倚赖图形主义(graphism)来铺设不同的世界图层,例如在第12章中,书写者只需要绘制一根线条便能将吴港和停泊于此的战舰同它们在铃的素描本上的形象连结起来。动画电影保留了角色面部轮廓线条的不连续性、以及脸颊和手臂处轻微的涂黑笔触,但与漫画不同的是,它对不同层次的知觉的并置主要是通过区分图形渲染(或基于线条绘制的渲染)和绘画渲染来实现的。有时,动画师还需要制作新的片段,例如染色的目标指示炸弹从天空落下的那一幕。漫画第26章用一个密密麻麻塞满了轰炸机剪影和炸弹的“超框架”(hyperframe)画格描绘了它们的威胁,然而在动画中最先出现的却是在蓝色背景前绽放的彩色烟雾、和伴随着这些彩色斑点的爆炸音效;在这之后,一根(由手握着的)画笔进入了画面,它将水彩颜料(其颜色与前面的烟雾相对应)甩打在天空/画布上,从而将实际的危险推延至另一个审美维度,而这则可以被解释为一种逃避现实的表现。

在漫画中,手自身也是主体,而这则是由物质性的方式,即不同的绘画类型所呈现的。就此而言,一个尤其引人注目的例子出现在第35章的中段,即延时炸弹爆炸后的第十六页。这一幕中,铃看着化为废墟的吴市,念出独白:在她眼中,那“就像我的左手所画出来的世界”[20]【译注7】;此后,河野在绘制图像时也真的这么做了——“中途呢,我决定用左手来绘制在这之后的所有背景。通常情况下,画的这么差劲的页面是不会被正式印刷出版的。”[21](这一点尤为突出,因为河野一直坚持手绘阴影线条,并回避使用网点。)在第35章中,铃从病榻上直起身,她所在的房间由河野的左手所绘制,因此,房间的木梁和窗格由颤抖的线条所构成,而在动画背景美术担当林孝輔的再演绎中,这些线条变成了同样由左手所绘制的,粗犷的厚涂笔触。[22]

由手所绘制的

近年来,漫画研究就文本与图像之间的合作提出了更加细致入微的看法,并探讨了文本和图像这两个研究方向内部的多样性。[23] 河野史代漫画作品的视觉元素(visual track)中有着异常丰富的图像格式。一些章节以图解的方式描绘了铁路线和时刻表,而其他章节则在描绘铃缝纫或下厨的画格,以及,作为这些活动之图示说明的画格(这不禁令人联想起信息图表)之间进行切换。在第29章,有连续六面的画页在页面上半部分中以铃的笔记本的形式再现了妇女们在防空课程中学到的东西;第4章用战时歌谣的歌词介绍了邻组(となりぐみ)的运作机制,而每一句歌词都伴有统一格式的画格,宛如连环画一般。第20章的画格甚至用它们的虚线边框模拟了衣服上的补丁,而这则影射了铃胡乱缝补衣物的方式。不过,所有这些格式有着一个共同点:它们都是由纯手绘(freehand drawing)的方式所产出的。即使是对城市空间与其建筑的描绘,也没有采用棱角分明的照相写实主义风格。印刷格式的招牌、海报和日历皆是经由「手」所再中介化的,而位于漫画叙事外(extradiegetic)的历史解释文段亦是如此:如图1所示,这段竖排排版的手写体日文被放置在跨页页中的空白间隙处。除了对定夺日本妇女战时日常生活的繁重体力劳动的描绘,河野的纯手绘也将这些被重新呈现(re-presented)的中介的“原始语境”,与铃,或更准确地说,铃的右手对它们的挪用连结在了一起。

但是,纵使纯手绘在《角落》中占据了主导地位,绘制线条自身的物质性还是会随着绘画工具的变化而改变。在绘制序章第一幕后的漫画时,河野将(钢笔)笔尖换成了(软笔)笔刷,并用高饱和度的黑色水粉勾勒/营造了夏日时分广岛湾区海涂的潮湿氛围。白木兰的回忆(第41章)是由胭脂刷绘制而成的;在当时,胭脂是游女专用的化妆工具,而兰将它送给了铃,并“劝告”她道:“拿去打扮得漂亮一些吧。大家都说...被空袭炸死的人,尸体看起来越漂亮的,会越早被清理呢。”[24] 不过,《角落》中最常出现的,是钢笔与铅笔之间的切换。钢笔的笔触所勾勒的,是叙境的当下(diegetic present),而颜色较浅的铅笔所勾勒的,则是铃的想象空间。从物质的角度来看,铅笔所描绘的也和铃在吴市的日常生活截然不同:印刷出版的漫画难以再现铅笔画的效果,所以,首先需要复制这些铅笔画,然后再将它们黏贴到作品上。讽刺铃的哥哥浦野要一的短篇漫画(共计五个单页),以及,与铃的过去和家乡有关、且反复在漫画中出现的苍鹭,都是由铅笔所绘制的。[25] 最初,铅笔画位于阐述了人物心理活动的对话框中——例如,在年幼的铃想象她所能买到的糖果时出现的对话框——不过,大部分铅笔画起到的是这两个作用:插入信息(像是明信片或邻组的回览板),以及,框定回忆与心理图像(作为画格边框)。就后者而言,最具代表性的例子,是紧接在延时炸弹爆炸之后的那一幕(第33章)。

纯黑的巨幅画格开启了这一篇章,在这之后则出现了一系列较小的、纯手绘边框的画格:起初,它们的连续性只是偶尔会被直尺描边的粗边框标准画格打断而已(见图1),但渐渐地,读者便会发现,这些铅笔手绘的画格正是铃的记忆碎片,它们闪回在铃发烧时做的梦中:与祖母的缝纫课、与兰的邂逅、与小晴美一同度过的时光...随着故事向前推进,方正的粗边框画格——以及由它们所框定的外部现实——在一系列的画格中逐渐占了上风,直到径子说出“杀人犯”一词为止。接下来的画页展示了前文所提到的,铃的右手的两种插画:其一,是轮廓脏乱、缠着绷带的残肢;其二,则是轮廓清晰的、健全的右手(见图2)。

由线条类型所构筑的这种差异化是高度媒介特异的(尽管这并不一定显而易见)。在这种特异性的影响下,动画电影将漫画第33章开头的单个纯黑巨幅画格扩展改编成了一整段影像,而根据片渊监督在分镜脚本上写下的手稿来看,这段动画脱离了赛璐璐动画的传统 (图层-叠加),而采用了“某种类似「电影-书法」(cine-calligraphy)的制作手法”[26],这也就是,由诺曼·麦克拉伦(Norman McLaren)在短片《瞬间的空白》(Blinkity Blink,1955年)中发扬光大的,直接在胶片上作画的技法。伴随着噼啪声,白色的线条在动画的这一幕中闪烁。与此同时,观众可以听到祖母的声音和铃的独白。接下来,背景(铃脚下的地面)由黑转白。在之后的那段彩色手绘动画里,铃(的身体)沿着一条由灰色线条所标示的、通往海边的小径奔跑,直至一切豁然开朗:处在前方的,是用蜡笔绘制的海港,以及,看得见听得着(却可望而不可及)的晴美。在《角落》的动画改编中,声音补偿了漫画画格之间的空隙(gutter)里的不可视内容。

杂志的物理特性!

河野并不是将《角落》作为一本漫画书,而是将其作为一部连载漫画来构思的,而且,她将《角落》发表在了一部从封面图像和漫画内容(指青年漫画)便能大致看出是主要面向男性读者的杂志上。[27] 在日本的语境下,河野的做法将“流派-性别化”(gendered genre)的议题摆上了台面。长相可爱的主角是在迎合普遍的(generically)男性凝视吗?一般的女性向漫画(feminine manga)元素是否被引流(fed into)到了男性(所主导的消费)领域之中?河野(的手)以及她笔下的铃的右手在《角落》中运用了各种各样的视觉形式——透过这一事实,我们可以发现,《角落》所展现的可能是一种以少女漫画的风格来削弱他者性的倾向。[28] 然而,河野的漫画却欠缺少女漫画中那些显著的形式特征:《角落》的大部分线条是用G笔所绘制的,而正是后者塑造了面向年轻男性的图像叙事(例如,劇画、青年漫)的画面。并且,在创作时,河野避开了少女漫画中经常使用的网点纸,以及,对印刷文字、和在两种以上的印刷字体之间进行明显轮换的这种形式偏好。

印刷文字在当代日本漫画中占主导地位:这既是为了提高可读性,也是为了实现审美透明性(也就是说,在不受物质因素的影响下接触角色和故事世界)。依照传统,手写体多用于拟声词的设计编排,而在女性向漫画流派的传统中,手写体则被用在那些外叙事的、且通常幽默风趣的,对人物和情形的评论上。[29] 然而,另辟蹊径的河野在创作时绕开了这种流派的传统。她的漫画并没有以印刷排版的文字(scripted text),而是以绘画性(pictoriality)来营造亲近感,例如铃笔下的画纸,再或,由左手所绘制的背景。河野笔下的对话框几乎都是由印刷文字所填充的。在对话框之外,她很少使用手写拟声词,直到漫画的后三分之一部分:当角色耳中的空袭警报声再也止不住时,拟声词便堆叠在画格之上,并呈现出一种绳索般的实质感(physicality)。

除此之外,河野的画格设计也并不一定就意味着《角落》便可以被归类到少女漫画的范畴中,因为,少女漫画更倾向于强调空间,且会反复地在画格与画页之间转移读者的注意力。同理,即使G笔在《角落》中发挥了重要的作用,我们也不能说《角落》便能因此被归为青年漫,尽管如此...青年漫通过画格与画格之间的过渡,从而突出了时间的流逝,而《角落》在这一点上与之相似——显然,在设计分隔画格的竖直空隙时略微使之不垂直对齐的河野史代,是在提请读者自己在漫画的画格与画格之间,以及,画页的阶层(tier)与阶层之间探索行进。而只有在描绘了并行情节(action)的那些平行蒙太奇中,画格才是对齐分割的。以第32章倒数第三页为例,在这里,画格的分割方式显而易见:铃和晴美正坐在防空掩体里躲避空袭,为了分散外甥女的注意力,铃在灰尘遍布的地面上画出了北条一家的面容。一连串竖直排列的拟声词将轰炸的威力和时长可视化,但是,在画页底层进行的画格分割所表现的与其说是时间的行进,不如说是时间的停滞:角色的视线(gaze),以及(在漫画阅读顺序的引导下)从右到左的读者的视线,受拟声词的重压而向下垂降,进而加强了这一幕的压迫感。

对印刷画页(printed page)的静止空间的这种关注,进一步体现在图像和文本物质性的偶发并置(occasional material juxtaposition of image and script)当中。当躺在病床上的铃无法区分现实与梦境时,一个水平分割的长方形画格突然出现在整个跨页的中层(第33章)。它复现了第15章中的一个画格(后者描绘了站在桥上的铃和周作以及他们映在水中的倒影),但现在,原本竖直排列的这个画格却沿顺时针方向旋转了45度。与顶层/底层的画格相比,(角色/读者)眼中的世界在这个画格里仿佛倒转了过来。然而,角色的声音却保持着过往的“标准姿态”(medial “normality”),这是因为,对话框中的日文对白仍是按往常那样竖排排版的。图像观看方向和文本阅读方向的这种并置,在河野史代第一部以广岛为主题的漫画中便已出现过:这便是29页的短篇漫画《夕凪之街》(夕凪の街,2003年发表)。[30]《夕凪之街》的主角,是一位对自己从原爆中幸存下来而感到愧疚的年轻女子。如图4所示,她突然沿着竖直分割的画格向上奔跑,想要远离曝尸荒野的死者。但是,每次当读者的目光随着女主的动作而向上移动时,她的独白——这一条条竖排排版的日文语句,这些应要从上往下阅读的文段——便会再次向下拉回读者的视线,进而,预示着女主的命运:无助的她,最终将摔倒在草坪之上。

图4. 河野史代第一部以广岛为主题的漫画《夕凪之街》中,图像与文本物质性的并置。河野史代,《夕凪之街 樱之国度》(夕凪の街 桜の国),东京:双叶社,2004年,页24-25. © 河野史代、双叶社,2004年

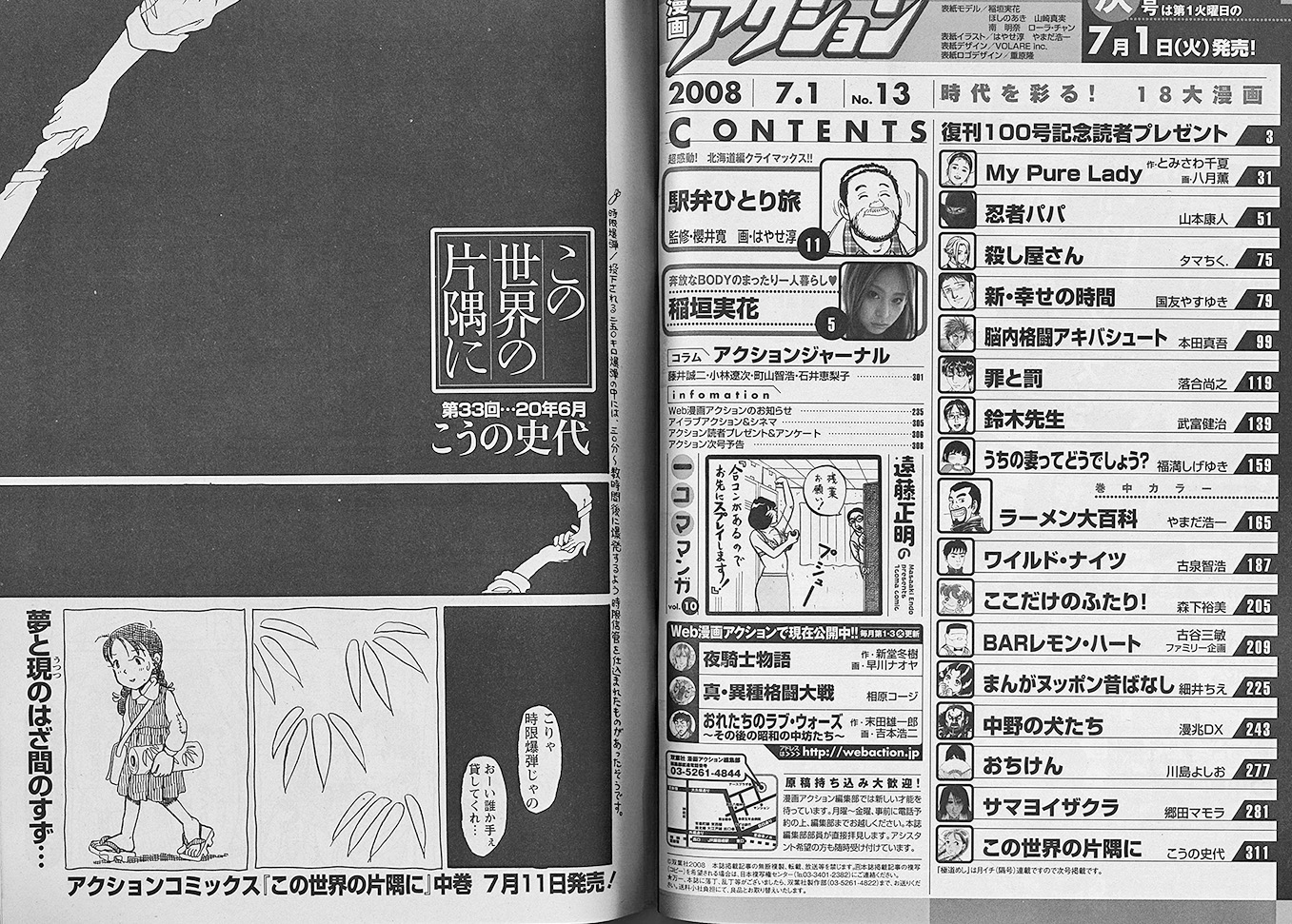

综上所述,河野的图像叙事显然打破了传统漫画流派(少女漫画/青年漫)的创作模式,除此之外,它甚至运用了漫画杂志的物理特性,以将自身与刊登在同一杂志的漫画的所属流派(即青年漫)区分开来——《角落》的连载章节被刊登在杂志尾部的目录页和杂志封底之间;事实上,它们占据了杂志的最后一页,或,杂志的“最角落”,仿佛在呼应漫画标题里的“角落”一般...(见图5、图6)

图5. 首次发表在《漫画ACTION》杂志2008年第13期(双叶社出版)的《角落》第32章的最后一页。跨页右页:右下角的页边距空白处写着邀请读者阅读下一期杂志的“次号へ!”。跨页左页:刊登了面向男性读者的约会网站广告。© 河野史代,双叶社,2008年

图6. 首次发表在《漫画ACTION》杂志2008年第14期(双叶社出版)的《角落》第33章的第一页。跨页右页为杂志目录,而河野的漫画排在目录最下方(对应第331页)。跨页左页的底部,为责编的布告:“《角落》第二卷将于2008年7月11日发售”;左下角的页边距空白处写着:“陷在梦境与现实之间的铃。” © 河野史代,双叶社,2008年

受欢迎的连载作品往往刊登在漫画杂志的最前面,而《角落》却隐世于杂志的最角落,宛如一部杂志附赠的、不需要被严肃对待的,插科打诨的“搞笑漫画”(ギャグ漫画)。[31] 这种有意在杂志内部进行的边缘式定位始于漫画第2章,即铃搬到吴市时;在广岛原爆的视角下,吴市即是世界史的边缘,或,世界史的“角落”。如第37章最后一页所示,从吴市望去,广岛的核爆云看起来并不像一团“蘑菇”。这幅图像体现了一个区域特异的边缘视角,不过,在漫画评论家吉村和真(Yoshimura Kazuma)的民族主义式解读下,吴市视角下的核爆云在它与“蘑菇云”这个由美国摄影所建构的符号的并置中重返中心,成为了日本的(象徵)。[32]

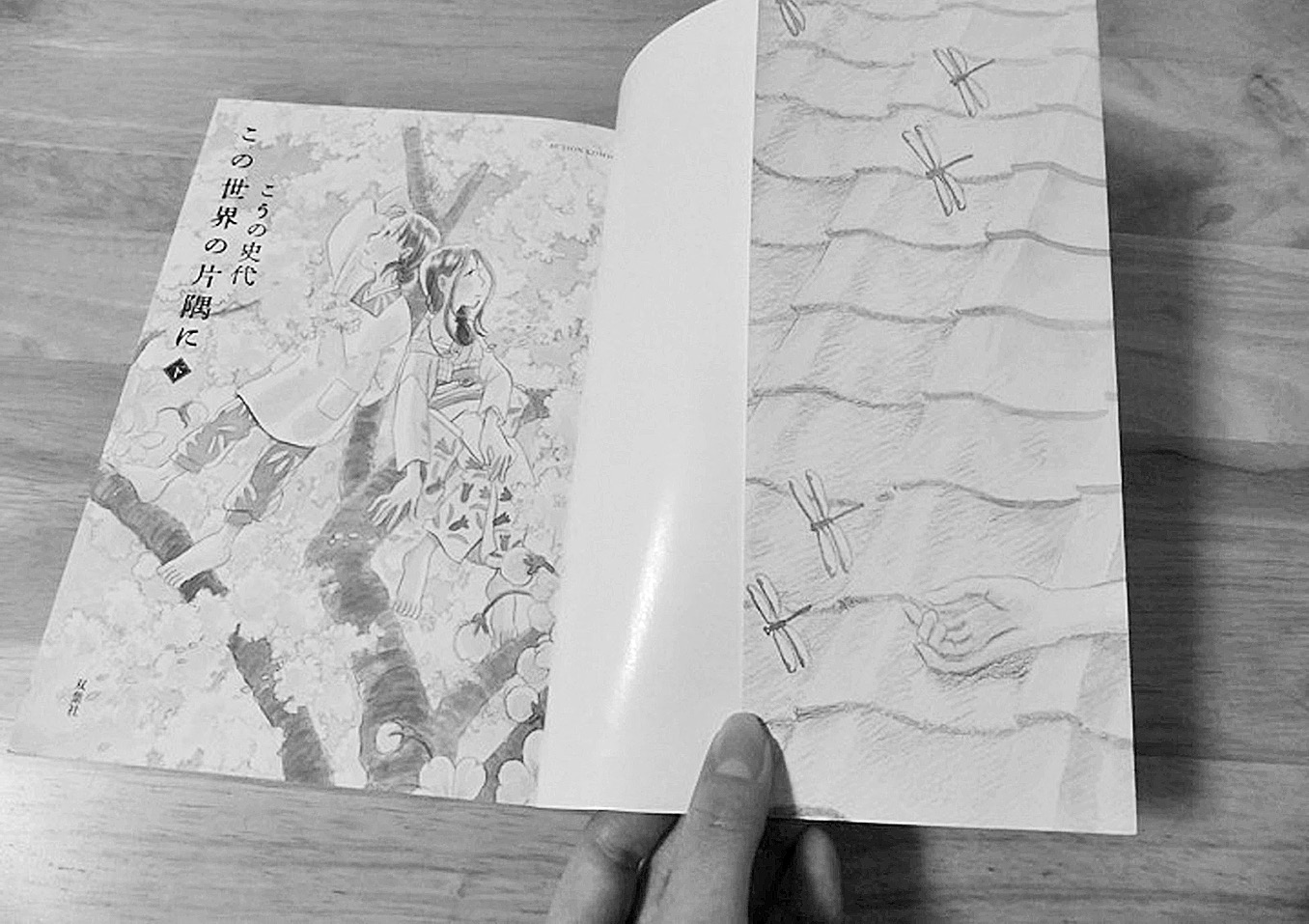

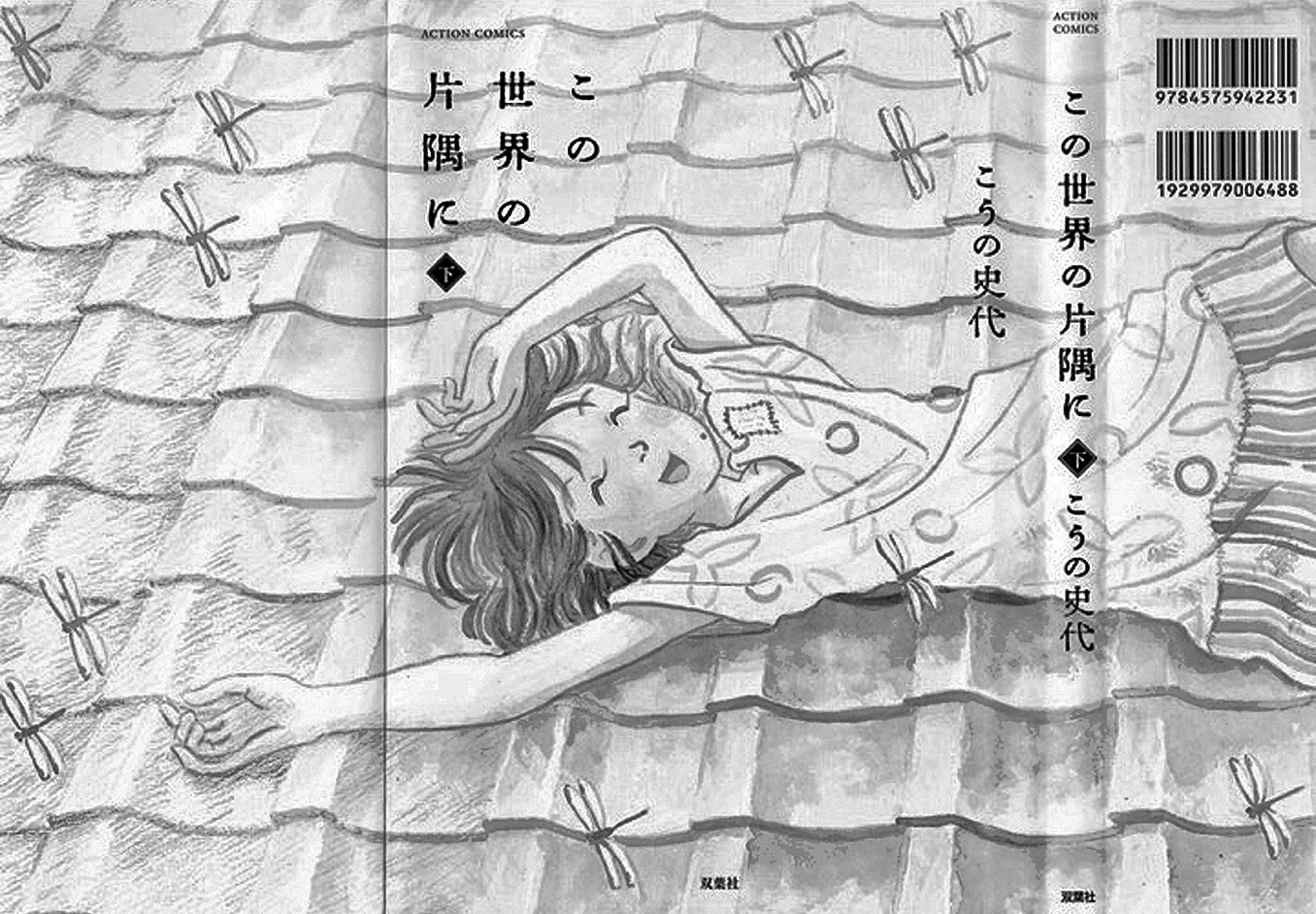

遗憾的是,铃的这段经历的物质-边缘性,却消失在了《角落》的再中介化过程中——最初因为两周一更而被分隔开来,分别位于2008年第13期和第14期杂志的“边角”的第32章最后一页和第33章第一页,却在单行本中构成了一个连续的跨页。同样失却的(在其他语言的译本中尤甚),还有连载格式与剧情-叙事时间的巧妙互动:《角落》第1章的扉页上写着“12月18日”,这不仅对应着昭和18年(1943年)的12月18日,而且还对应了平成18年(2007年)的12月18日,也就是这一章的发表日期。很明显,漫画各章的标题“保守地”引用了皇历,由此,《角落》再次将过去和当下连结了起来——例如,根据皇历,大日本帝国1945年的覆灭并不意味着裕仁天皇执政的终止(毕竟昭和年代从1926年一直持续到了1989年)。最后值得一提的是,日版单行本第3卷的护封不着痕迹地预示了叙事将要推向的悲剧性高潮:仰面躺在屋顶上的铃伸直了自己的右臂,但她的右手却和护封一起向内折叠,或者说,被护封切断...(见图7、图8)在其他场合,这种分割很容易被忽视,譬如,那些更倾向于展出由单一画框框定的完整彩绘,而不是被分为多个画格的黑白单页的,画展。

图7. 读者手中的《角落》日版单行本第3卷的护封。

图8.《角落》日版单行本第3卷的书套,展开后的效果。© 河野史代,双叶社,2009年

结语

《谢谢你,在世界的角落找到我》是一部以“连结”为母题的作品:它连结了日本的战时过去和(在当代日本[漫无止境的日常中])正在逐渐消解的当下,连结了政治色彩浓厚的历史与更容易产生共鸣的个人绘画动作,并且,连结了触感的参与和批判性的静观冥想(contemplation)。《角落》有意识地运用了根植于日本媒介景观的、日本漫画特有的物质性来实现前文所述的“连结”,因此,它的一部分效果可能会在翻译过程中丢失。作为场域(site)的印刷画页连结了多个画格,进而呈现了许多不同的视角——评论家中村唯史强调了这种操演所涉及的,主体性与客体性(亦或,想象界与实在界)的相互作用,并认为,这种互动是日本漫画媒介(尤其是河野史代作品)的普遍特征。《角落》既不偏袒任何一种创作技法,也没有在诸多创作技法的交叠中呈现出一幅“融合怪”似的景观,而是在它们之间保持着微妙的平衡,无论是在同一画页的同一空间中并置不同类型的线条、重新手绘各种印刷品(printed matter),还是,将「手」从铃那里抽离出来(就角色本体论的角度来看)。归根结底,阿铃是无法通过幻想来逃避残酷的社会现实的。日本漫画作为一种高度情感化(affective)的流行媒介,一直在推动着某种类似于世界系的、主体性与客体性之间的相互关系——“世界系的特征,是微观境况-主角的家庭与学园、与宏观境况-世界性(global)危机和毁灭之间的,换而言之,‘我’与‘世界’之间的,直接联系。”[33] 相比之下,《角落》并没有使社会缺席,而是向处于接收端(receptive)并对边缘相关议题敏感的读者提供了丰富的历史知识。

但是,正如本文导言部分所示,日本漫画的媒介特异性既包括美学形式,亦包括社会-文化意义上的倾向/秉性。纯手绘、铅笔的使用、对触感的强调、对先前流派的背离(indifference),以及,作品中历史现实主义的充盈与语义直接性之匮乏【译注8】的并存...就这些元素而言,《角落》显然偏离了日本和全球市场中贩售的所谓“正统漫画”(manga proper)的范畴。与此同时,《角落》这部图画叙事无疑具有鲜明的“日漫”特征,不论是杂志连载的出版方式、可爱角色的中心地位,还是优先于批判性间离效果的亲近感营造和情感参与。介于高雅文艺(或言“美学秉性”)与工业-大众文化(或言“大众秉性”)的现代二分法之间的,是那些“中額”作品("middlebrow" fiction),然而,与其说河野创作的《角落》仅仅是此类作品的另一种变体(尽管语言不同),不如说她所描绘的“连结”,与最近的粉丝/同人文化的「以想象为导向的(美学)秉性”」(imagination-oriented disposition)有着异曲同工之妙——后者融合了美学秉性中的专业知识,与大众秉性对共享的爱好。[34] 从物质性的(而非表征)角度去关注各种艺术形式,或许将有助于阐明这种跨领域的“第三”秉性。

译注

0. 总声明:英文括弧“(...)”中的内容为译者的补充,而中文括弧“(...)”里的内容则是调整后的原文语段。

1. 参见「表象文化論」(ひょうしょうぶんかろん、Studies of Culture and Representation)。这次在翻译“representation/represent/representational”时,译者首次选择了日本文化批评语境中的“表象”译法;或许,这会更符合(正逐渐受日本文化研究-话语影响/渗透[中义]的)大陆读者的阅读习惯...?在后文,视不同语境,译者将采用“表征/表象/再现...”的译法。

2. 借用村上龙的小说标题:战争在海对岸开始。

3. 这里可以理解为:让读者继续阅读下去,或者...让读者跟随铃一同前往吴市?

4. 它可以被理解成:不受画格框定的、任右手自由发挥的,空白的空间,再或...一片远离战争影响的空间?

5. 原文为“June, year 18.”此处疑为作者的笔误,因为漫画原文确确实实是昭和20年。

6. 虚构的漫画书页里所描绘的(画格-画纸的)卷页效果,和读者的动作(翻页的时侯可能真的会让书的边角卷起来...另一种情况是,读者需要在翻页前压住卷起来的纸页)之间有着重叠。

7. 文中对漫画文本的翻译均参考自台版单行本《謝謝你,在這世界的一隅找到我(上)》与《謝謝你,在這世界的一隅找到我(下)》。

8. 直译自“lack of semantic straightforwardness”,或许,这指的是《角落》含糊的“政治站位”...以至于观众时至今日还是会不由自主地沉浸在“反战还是反战败”的钝感争辩当中。

附录

本篇论文最初是为德国媒介研究协会(German Association of Media Studies,GfM)内的“动画”和“漫画”研究工作组于2016年11月在汉诺威举行的联办年会所撰写的主题讲稿;本文也是这篇文章的修订版——杰奎琳·伯恩特:<“手中手”:河野史代漫画 [谢谢你,在世界的角落找到我] 与片渊须直改编动画电影的对比>(Hand in Hand: Kouno Fumiyo’s Mangaserie Kono sekai no katasumi ni (In this corner of the world) im Vergleich zur Anime-Adaptation durch Katabuchi Sunao),《手工性的美学:对动画与漫画研究的跨学科贡献》(Asthetik des Gemachten: Interdisziplinare Beitrage zur Animations-Und Comicforschung),汉斯-约阿希姆·巴克(Hans-Joachim Backe)、裘莉娅·埃克尔(Julia Eckel)、埃尔温·费耶辛格(Erwin Feyersinger)、维罗尼卡·辛娜(Véronique Sina)、扬-诺尔·索恩(Jan-Noel Thon)编辑,柏林:德古意特出版社,2018年;开放获取版本:https://www.degruyter.com/view/product/485366?format=EBOK,2018年10月18日读取

1. 起初,《角落》的真人改日剧(于2011年8月5日播出的,日本电视台的终战纪念特别剧:終戦記念ドラマスペシャル 「この世界の片隅に」)并没有掀起多大的波澜。2016年上映的改编动画电影意外走红后,TBS制作并播出了另一部改编自《角落》的迷你电视剧(2018年7月至9月放送,每集长54分钟,总计9集)。动画电影的加长版(この世界の(さらにいくつもの)片隅に)于2019年12月上映。

2. 约翰·基洛利:<媒介概念的起源>(Genesis of the Media Concept),《批评探索》(Critical Inquiry),第36卷、第2期(2010年冬季),页324.

3. 扬·贝滕斯(Jan Baetens)、雨果·弗雷(Hugo Frey)、斯蒂芬·E·塔巴契尼克(Stephen E. Tabachnick):<导言>,《剑桥图画小说史》(The Cambridge History of the Graphic Novel),剑桥:剑桥大学出版社(Kindle版),页10-11.

4. 河野史代:《谢谢你,在世界的角落找到我(上)》,东京:双叶社,2008a;河野史代:《谢谢你,在世界的角落找到我(中)》,东京:双叶社,2008b;河野史代:《谢谢你,在世界的角落找到我(下)》,东京:双叶社,2009年;河野史代:《在这世界的角落(总集篇)》,洛杉矶:七海出版社(Seven Seas Entertainment),2017年.

5. 山代巴:《在这世界的角落》(この世界の片隅で),东京:岩波新書,2007年再版(1965年初版)

6. 罗比·柯林(Robbie Collin):<东京电影节影评:[角落] 如梦如幻地描绘了在广岛原爆中消失的事物>(Tokyo Film Festival Review: In This Corner of the World Is a Dream-like Portrait of What Was Lost in the Blast of Hiroshima),《每日电讯报》(网络版),2016年10月28日,https://www.telegraph.co.uk/films/0/in-this-corner-of-the-world-review-a-dream-like-portrait-of-what/,2018年10月18日读取.

7. 参见进一步的讨论——竹内美帆(Takeuchi Miho):<河野史代的广岛漫画:以风格为中心的再阅读尝试>(Kouno Fumiyo’s Hiroshima Manga: A Style-Centered Attempt at Re-reading),《Kritika Kultura》,第26卷(2016年),页243-257,https://journals.ateneo.edu/ojs/index.php/kk/article/view/KK2016.02613,2018年10月18日读取;本文的DOI为http://dx.doi.org/10.13185/KK2016.02613

8. 马克·席林(Mark Schilling):<[角落]:片渊的战争动画满溢人文关怀>(In This Corner of the World: Katabuchi’s War Film Has a Human Heart),《日本时报》(网络版),2016年11月19日,https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2016/11/16/films/film-reviews/corner-world-katabuchis-war-film-human-heart/#.W9CGAy97HsE,2018年10月18日读取.

9. 河野史代、西岛大介:<对谈:来自角落的爱>(片隅より愛をこめて),《ユリイカ》特辑(2016年12月),页39.

10. 細馬宏通:《两个<角落>:漫画与动画的声音和动作》(二つの「この世界の片隅に」―マンガ、アニメーションの声と動作),东京:青土社,2017年,页160.

11. 河野史代、Kayama Ryushi:<河野史代的特别访谈>,《谢谢你找到我们:<角落>官方同人集(漫画ACTION)》(ありがとう、うちを見つけてくれて 「この世界の片隅に」公式ファンブック (アクションコミックス))东京:双叶社,2017年,页189.

12. 卡塔琳·欧尔班:<划痕与缝线的语言:处在超阅读与印刷之间的图画小说>(A Language of Scratches and Stitches: The Graphic Novel between. Hyperreading and Print),《批评探索》(2014年春),页171.

13. 参见欧尔班,<划痕与缝线的语言>,页173.

14. 劳拉·U·马克斯:《触觉:感官理论与多感官媒介》(Touch: Sensuous Theory and Multisensory Media),明尼阿波利斯:明尼苏达大学出版社,2002年.

15. 夏目房之介:《漫画为何有趣?它的表现形式与语法》(マンガはなぜ面白いのか―その表現と文法),东京:NHK出版,1997年;参见书中卢卡斯·R·A·王尔德(Lukas R. A. Wilde)的论文.

16. 迈克尔·陶西格:<绘画想要的是什么?>(What Do Drawings Want?),《文化、理论与批判》(Culture, Theory and Critique),第50卷、第2-3期(2009年),页271;本文的DOI为10.1080/14735780903240299.

17. 约翰·伯格:《伯格论绘画》(Berger on Drawing),吉姆·萨维奇(Jim Savage)编,伦敦:Occasional出版社,2007年,页3.

18. 参见竹内美帆,<河野史代的广岛漫画>

19. 河野史代:<守旧的女人>,《わしズム》,第19卷(2006年),页9-15.

20. 参见河野史代,《在这世界的角落(总集篇)》,页346.

21. 福間良明、山口誠、吉村和真:<专访河野史代:非体验与漫画表现>([インタビュー]こうの史代――非体験とマンガ表現),《广岛的多重面相:战后记忆史与媒介力学分析》(複数の「ヒロシマ」 記憶の戦後史とメディアの力学),福間良明、山口誠、吉村和真编,东京:青弓社,2012年,页380.

22. 藤津亮太:<采访美术监督林孝輔>(Intabyu bijutsu kantoku Hayashi Kosuke),《<角落>动画电影官方指南》(この世界の片隅に 劇場アニメ公式ガイドブック),东京:双叶社,2016年,页83.

23. 南希·佩德里(Nancy Pedri):<在漫画中混合视觉媒介>(Mixing Visual Media in Comics),《ImageTexT》,第9卷、第2期(2017年),http://www.english.ufl.edu/imagetext/,2018年10月18日读取.

24. 参见河野史代,《在这世界的角落(总集篇)》,页283.

25. 参见細馬宏通,《两个<角落>》,页55.

26. 《角落》制作委员会编:《<角落>剧场版动画分镜集》(この世界の片隅に 劇場アニメ絵コンテ集),东京:双叶社,2016年,页487;在日本,“电影-书法”被称为“杵书”(kine calligraph),参见玛利亚·罗贝塔·诺维耶利(Maria Roberta Novielli):《漂浮的世界:日本动画简史》(Floating Worlds: A Short History of Japanese Animation),博卡拉顿:泰勒-弗朗西斯出版社,2018年,页47;值得注意的是,诺维耶利的论述忽略了麦克拉伦;负责这段“电影-书法动画”的,是演出助理野村健太,参见細馬宏通,《两个<角落>》,页70.

27.《漫画ACTION》于1967年创刊,并在2004年改为双周刊;在六七十年代,它还是一本主要刊登剧画的漫画杂志;这本杂志因Monkey Punch的《鲁邦三世》,小池一夫原作、小岛刚夕作画的《带子狼》(子連れ狼),以及臼井仪人的《蜡笔小新》等作品而声名鹊起。

28. 黛波拉·沙蒙(Deborah Shamoon):《热情的友谊:日本少女文化的美学》(Passionate Friendship: The Aesthetics of Girls’ Culture in Japan),檀香山:夏威夷大学出版社,2012年;藤本由香里:《我的安身之处到底在哪?少女漫画映射出的心之形状》(私の居場所はどこにあるの? 少女マンガが映す心のかたち),东京:學陽書房,2008年再版(1998年初版)

29. 吉安卡菈·温瑟-舒茨(Giancarla Unser-Schutz):<通过语言模式,重新定义少女与少年漫画>(Redefining Shojo-and Shonen-Manga via Language Patterns),《跨媒介的少女:探索当代日本的“少女”创作技法》(Shojo Across Media: Exploring “Girl” Practices in Contemporary Japan),杰奎琳·伯恩特、長池一美、大城房美编,纽约:帕尔格雷夫·麦克米伦出版社,2018年,页72-73.

30. 河野史代:《夕凪之街 樱之国度》(Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms),雨宫直子(Naoko Amemiya)、安迪·中谷(Andy Nakatani)译,旧金山:Last Gasp出版社,2006年.

31. 堀井憲一郎:<我们不应该将[角落]的改编电视剧视为一部战争剧>(ドラマ『この世界の片隅に』は、戦争ドラマとして観てはいけない),gendai.ismedia.jp(現代ビジネス),https://gendai.ismedia.jp/articles/-/56642,2018年7月22日发表,2018年10月18日读取.

32. 吉村和真:<漫画所再现的“广岛”:从“风景”的角度解读>(マンガに描かれた「ヒロシマ」―その“風景”から読み解く),《广岛的多重面相》,2012年,页181-182.

33. 中村唯史:<论漫画中感知与认知的表象——以河野史代的作品为中心>(マンガにおける知覚·認識の表象をめぐって——こうの史代の作品を中心に),《当代视觉表象中的媒介/中介化身体研究》(現代視覚表象におけるメディア的身体の研究),阿部宏慈、中村唯史编,山形市:山形大学人文学部出版,2015年,页87.

34. 佐尔坦·卡苏克(Zoltan Kacsuk):<从‘游戏性写实主义’到‘以想象为导向的美学’:从日本漫画和御宅族理论出发,重新审视布迪厄对同人研究的贡献>(From “Game-like Realism” to “Imagination-oriented Aesthetic”: Reconsidering Bourdieu’s Contribution to Fan Studies in the Light of Japanese Manga and Otaku Theory),《Kritika Kultura》,第26卷(2016年),页274-292.

作者介绍

截止发稿时,杰奎琳·伯恩特是斯德哥尔摩大学日本语言与文化系的正教授。1991至2016年间,她在日本任教,并最终在京都精華大学的漫画学部取得了正教授职称。她分别于1987年和1991年在柏林洪堡大学取得了日本研究的学士学位、与美学/艺术理论(Kunstwissenschaft)的博士学位。伯恩特的学术作品专注于研究图像叙事、日本动画、与现代日本艺术,并受到了媒介美学与展览研究(exhibition studies)的影响。她用日语、德语和英语发表过许多研究作品,例如,与他人合编的《日本漫画的文化交汇点》(Manga’s Cultural Crossroads,2013年),以及专著《日本漫画的现象》(Phänomen Manga,1995年)和《日本漫画:媒介、艺术与物质》(Manga: Medium, Art and Material ,2015年)。更多信息,另请参见教授的个人网页——https://jberndt.net

In recent years, content-driven, or representational, readings of anime and manga have been increasingly countered by mediatic approaches, but the main focus has been mainly on the materiality of platforms and institutions rather than that of signifiers and artifacts that afford certain mediations in the first place. Kouno Fumiyo’s In This Corner of the World (Kono sekai no katasumi ni) provides an excellent case to explore manga’s aesthetic materiality, last but not least because of its congenial adaptation to the animated movie of the same name directed by Katabuchi Sunao (Studio MAPPA, 2016). [1] This movie attests to what John Guillory has pointed out in a different context, namely, that “[r]emediation makes the medium as such visible.” [2] Consequently, it is used below as a foil to highlight how Kouno’s manga conjoins different materialities in a medium-specific way resting on the drawn line, print on paper, and the serial format of the narrative.

This article pursues manga mediality from the angle of materiality to approach forms as aesthetic affordances without reiterating a decontextualized formalism modeled on modernist notions of authorship and autonomous art. First, I will try to summarize the story as unimpaired as possible by considerations of medium specificity in order to demonstrate subsequently what attention to aesthetic materiality may lead the reader to see or rather to become: namely, a mature participant. Second, I focus on the precedence of hand-drawing as well as the variety of drawn lines, pointing out that in Kouno’s case aesthetic materiality does not facilitate authorship (evinced by traces of the artist’s hand) or the manga medium as an art form (evinced by modernist self-reflexivity as an attribute of the text itself), but commonality, a distributive agency that involves artist, characters, and readers bridging past and present. Then, I turn to what is more often associated with materiality, namely, the physicality of the publication medium. Instead of paper quality (i.e., the coarse and yellowish printing paper of Japanese editions so difficult to reproduce abroad), I foreground linework, lettering, and paneling as well as the physical placement of the individual installments within the magazine. I interpret these aspects as nonverbal statements about genre conventions and also correlate them with the theme of marginality touched upon already in the work’s title. As a whole, I hope to demonstrate that the focus on manga materiality in the broad sense (that is, including a non-representationalist attention to forms of representation, mediation, distribution, and perception) allows for critical readings of popular fiction that acknowledge its inclusive potential.

In the course of the discussion, I refer time and again to aspects that distinguish In This Corner of the World from conventional manga as represented by the global bestsellers. Characteristic of Kouno’s work is a conjoining of not only actors and times but also dispositions: it keeps with mangaesque conventions and twists them concurrently, occupying a third space between major franchise-prone productions and highly authorial expressions. While such a disposition applies to a significant number of Japanese graphic narratives—stretching from Tezuka Osamu and Ikeda Riyoko to Taniguchi Jiro, Asano Inio, and Kyo Machiko—it still easily escapes European or North American comics studies insofar as they are inclined to neatly sort between “graphic novels” as serious personal and political narratives on the one hand, and “comics and manga” as industrial, coded, and serial B-literature on the other hand. [3] Against this backdrop it raises wrong expectations to call manga like Kouno’s “alternative,” even if they appear slightly deviant within the mediascape that is locally and globally associated with Japan.

A Hand’s Tale

Kouno’s graphic narrative was serialized in the biweekly magazine Manga Action from January 2007 to January 2009. Whereas the Japanese book edition falls into three volumes, the translated English edition crams the whole 430 pages into one unwieldy volume to accommodate a type of consumption that rests less on serialization than in Japan. [4] In line with the structure of the original magazine series, the book edition begins with 3 unnumbered prologue chapters, which are followed by a total of 44 numbered chapters and one “Final Chapter,” each forming a more or less self-contained short episode of mostly 8 (sometimes 12, 14, or 16) pages and ending with a punchline.

In This Corner of the World is the story of Suzu, a humble young woman who grows up in the Hiroshima delta, approximately 3 km away from the later epicenter of the atomic bomb. The actual plot begins in February 1944, when the nineteen-year-old is married off to the neighboring town of Kure. There she cooks, scrubs, and cares for her sick mother-in-law while the men are at work—her husband, Shusaku, as a minor clerk at the navy’s court-martial and her father-in- law as an engineer at the shipyard of what was then the largest naval base of the Japanese Empire. Foreign in this corner of the world and constantly scolded by her sister-in-law Keiko, Suzu has but one refuge: drawing. Already as a little girl, she compensated for her older brother’s bossiness by depicting him as an ogre in short comic strips. In her new setting, drawing helps her to cope with the unfamiliar environment while keeping the repercussions of war at bay. In June 1945, Suzu loses both her niece Harumi and her right hand to a delayed-action bomb. Months later she learns of the death of her parents and the radiation sickness of her younger sister in Hiroshima, from where Suzu and Shusaku take an orphan home in the end.

The manga’s title refers to a collection of nonfictional texts, first published on the occasion of the twentieth anniversary of the Hiroshima bomb. But whereas that volume accentuated the place (kono . . . katasumi de: “in this corner”) and Hiroshima at that, [5] Kouno uses a particle that may also indicate a direction (kono . . . katasumi ni: “into this corner”), connoting both the protagonist’s move to another town and the reader’s orientation to the war-time past. The animated movie of 2016, which drew broad public attention to Kouno’s narrative, fueled primarily two readings of it: on the one hand as a war story, on the other as “a period drama about female forbearance” [6] (both more or less underpinned by the postwar discourse of Japanese self-victimization through feminization). [7] Whereas film critics found the war responsibility inadequately addressed, [8] the manga artist herself said that she wanted to show Hiroshima from a perspective other than the one naturalized in Japan: “Somehow I felt reluctant to watching and depicting things related to the atomic bomb. I think I don’t like the fact that the ‘atomic bomb’ is immediately linked to ‘peace.’ As if it had bestowed peace on us!” [9]

Yet, the war is not the only driving narrative force, neither in the manga nor the animated movie. Although the movie gives the male characters more space and extends the social spectrum through their jobs, the women are at the center, Suzu and, as her counterpart, Keiko, who had been a modern girl and married out of love, but once widowed is to hand over her son to the in-laws and on top of that, to see her house in Kure’s downtown demolished for firebreaks. The third historical type of woman is the courtesan Rin, whom Suzu encounters when she loses her way in the city, and who perishes in the bombardment of July 1945 together with the red-light district of Kure. The animated movie of 2016 marginalized Rin and concealed Shusaku’s premarital relationship with her, which facilitated its promotion as a story of growing marital love outside of Japan.

In view of the manga’s remediation by the animated movie, In This Corner of the World appears to tell not only of war and love, but also of a drawing hand. Hosoma Hiromichi, who published a collection of meticulous observations on both works, maintains that the animated movie shifted the narrative’s perspective completely from Suzu to her right hand. [10] Kouno herself acknowledged that shift for the third volume of the Japanese edition, stating in an interview, “that from this point on, it is the story of the hand.” [11] As if heading for this shift from the outset, occasional panels feature a single hand placed against empty ground. This starts with the third prologue episode: In the last small panel on the bottom left (according to the Japanese reading direction just before turning the page), a hand holding a pencil stub appears; eighteen pages—and, for Suzu, five years—later this panel reappears, except that now chopsticks point to the left propelling the reader forward. After the explosion of the delay-action bomb on the last page of chapter 32 (Figure 1), when it becomes clear that Suzu has lost not only her niece but also her drawing hand, the hand begins to lead a life of its own, first as a mental image: A panel with the bandaged arm stump is followed by one with the complete hand which sketches a shamrock that grows into a garden of paradise, with Harumi playing in it (Figure 2). In chapter 39, the hand descends from above and strokes consolingly Suzu’s head as she kneels in her vegetable patch crying on August 15, 1945, after the Emperor’s radio speech. And at the very end of the manga the hand even gains its own voice. Holding a pen, it opens the last chapter, and after having spoken to Suzu in the form of a letter composed of panels and handwritten monologue, it becomes visible again, sequentially placed in free space and now holding a brush with which it watercolors the remaining pages.

Figure 1. Right: the last page of “Chapter 32 (June, year 18)”, left: the first page of“Chapter 33 (June, year 18 [1945]).” Kouno Fumiyo, Kono sekai no katasumi ni, ge (In This Corner of the World, III) (Tokyo: Futabasha, 2009), 36–37. © Fumiyo Kouno, Futabasha 2009.

Figure 2. The return of the lost hand. Kouno Fumiyo, Kono sekai no katasumi ni, ge (In This Corner of the World, III) (Tokyo: Futabasha, 2009), 42–43. © Fumiyo Kouno, Futabasha 2009.

Haptic Participation

But in Kouno’s manga the hand is far more than a motif that attracts attention to what it represents. Before any symbolism, it serves a pragmatic function, namely, to invite the reader into the storyworld. Whereas conventional manga employ close-ups of character faces, here close-ups of the hand assume that role. This already appears in the third prologue episode when Suzu is given a pencil by her classmate Mizuhara to do a drawing in his stead. While the right half of the double-page spread relates the situation in seven ruler-rimmed panels, the left half features two hand-drawn and almost empty rectangles that are slightly shaded on the lower left (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Suzu drawing. Kouno Fumiyo, Kono sekai no katasumi ni, jô (In This Corner of the World, I) (Tokyo: Futabasha, 2008a), 45. © Fumiyo Kouno, Futabasha 2008.

The upper one contains a tail-less speech balloon with Suzu’s words; the lower one shows her hand drawing a brush stroke to the right, flanked by two more bubbles. Suzu’s forearm, however, is part of the frame, which at this point bulges into the panel. As distinct from the animated movie, the comics medium is capable of making Suzu’s hand the entry point to an empty space, which is at once the protagonist’s drawing paper and the manga page in the reader’s hand. The ensuing sensation of overlap is heightened on the following double-page spread, where the paper is drawn as if rising at the edges. Thus, the reader conjoins the protagonist in a concurrently representational and material way.

Discussing the specificity of comics as a paper-based medium and its persistence in the digital age, Katalin Orbán has highlighted how much comics rest on “print text [being] experienced as permanently integrated with its material base.” [12] In reference to Alois Riegl, Orbán observes that “the sense of materiality is thus established mostly through a tactile relationship, in which hand-book contact and haptic visuality mutually inform each other.” [13] While Laura U. Marks exemplified haptic vision with regard to video imagery and its grain, [14] in manga—a type of comics defined primarily as “line picture” (senga) [15]—haptic vision as an embodied form of seeing rests mainly on the drawn line. Drawing is one means of approximation, as anthropologist Michael Taussig observes: “A line drawn is not important for what it records as much as what it leads you to see.” [16] This is inspired by John Berger’s account of drawing, who actually went further than seeing: “Each confirmation or denial brings you closer to the object, until finally you are, as it were, inside it: the contours you have drawn no longer marking the edge of what you have seen, but the edge of what you have become.” [17] Berger understands drawing primarily as an autobiographical record and applies it to the becoming of the artist, whereas in Kouno’s manga the personal act of drawing goes beyond individualism; it serves commonality—between the characters as well as between artist, characters, and the readers who are being taken by hand and invited to eliminate historical distance, not simply looking at the past, but literally touching it. [18]

Kouno had previously experimented with such closeness in the six-page colored short story “Furui onna” (An old-fashioned woman, 2006). [19] Again, the protagonist is a young woman who appears to submit silently to Japan’s modern patriarchy, and again she is an amateur artist, except that this time she draws on the bare back of leaflets. Emulating such a support, the pages on which the manga panels are laid out are imprinted with faint mirrored patterns, which seem to shine through from the leaflet’s front. While this does not necessarily catch the eye upon first reading, on closer inspection it may ironically undercut the verbal affirmation of patriarchy and nationalism. Here as elsewhere, Kouno calls upon her audience to maturely engage, at the risk of remaining politically vague herself.

In contrast to the water-colored “Furui onna,” the monochrome manga In This Corner of the World leans exclusively on graphism for layering different worlds, such as when it takes only one drawn line to conjoin the Bay of Kure and its battleships with their image in Suzu’s sketch book (in chapter 12). The animated movie retains the discontinuous outlines of characters’ faces and the little strokes on cheeks and arms, but it juxtaposes the different levels of perception primarily through distinction between graphic, or linework-based, and painterly renderings. Occasionally new sequences had to be created, for example, in the case of the colored target-marking bombs. While the manga relates their threat in one densely packed “hyperframe” panel in chapter 26, the animated movie first shows spots of color on a blue background, accompanied by sounds of detonation, before a hand with a brush enters the screen to set just such paint splotches onto the sky, thereby deferring the actual danger to another, aesthetic dimension, which can be read as escapism.

In the manga, the hand also presents itself as the subject materially, that is, through the very type of drawing. A particularly striking example appears in the middle of chapter 35, sixteen pages after the explosion of the delayed-action bomb. Here, Suzu monologizes in view of the ruined city of Kure, that it appears to her “as a world drawn with my left hand,” [20] which Kouno actually follows through with in her drawing of the images: “Halfway I decided to draw the background consistently with my left hand. Normally you would not get pages of such poor quality printed.” [21] This especially stands out, as Kouno keeps to hand-drawn hatching, eschewing the use of screen tone. Due to her left-handed rendering the bars and struts of the room where Suzu sits in her sickbed futon (in chapter 35), consist of shaky lines, which the background artist of the animated movie, Hayashi Kosuke, turned into broad impasto strokes, also brushed with the left. [22]

Drawn by Hand

In recent years, comics studies have advanced a more differentiated view on the collaboration between text and image, exploring variety within each of the two tracks. [23] The visual track of Kouno’s manga is exceptionally rich in image formats. Some chapters contain diagrammatic representations of railway lines and timetables; others switch between panels that show Suzu sewing or cooking, and panels that serve as pictorial instructions for those activities, reminiscent of infographics. What the women learn in the air defense lessons is related through Suzu’s notebook on the top half of six consecutive pages in chapter 29, and how the neighborhood association works is introduced in chapter 4 through the lyrics of a war-time song, the lines of which are accompanied by uniform picture boxes. In chapter 20, the panels even mimic dress patches with their dashed edges, alluding to Suzu’s haphazard way of mending. But all these formats have in common that they are executed as freehand drawing. Not even urban spaces and their buildings assume a sharp-edged photorealistic look. Printed signs, posters and calendars are remediated by hand as are the extradiegetic historical explanations, placed as vertical Japanese script in the inner page margin (Figure 1). In addition to the laborious manual work that determined women’s everyday life during the war, Kouno’s freehand drawing associates both the “original contexts” of the re-presented mediums and their appropriation by Suzu or, more precisely, her hand.

But as dominant as free-handed drawing may be, the materiality of the drawn line itself changes with the tools. After the first prologue chapter, Kouno swaps the manga pen nib for a brush, evoking with water-saturated black ink the humidity of a summer’s day in the tidal mudflats of Hiroshima Bay. The memories of Rin are rendered with a rouge brush, the utensil of the courtesan, which Suzu received from her with the advice: “Go on and make yourself pretty. / You know what they say . . . / When they clean up the bodies after a bombing, they start with the prettiest ones.” [24] The most common alternation, however, is that between pen and pencil. While the pen stroke marks the diegetic present, the paler pencil outlines the domain of Suzu’s imagination. It also sets itself apart from her everyday life in Kure materially: as pencil drawings are difficult to reproduce in printed manga, they were first copied and then glued into the artwork. A pencil is used for the short comic strips that caricature the older brother (five individual pages in total) as well as for the recurring heron, that associates with Suzu’s past and hometown. [25] At the beginning, pencil drawings are located in thought bubbles—for example, when little Suzu pictures the candy she could buy—but mostly they serve two purposes: informative inserts (postcards or the neighborhood circular, for example) and panel frames that enclose retrospectives or mental images. The most representative example of the latter is the sequence in chapter 33 right after the explosion of the delayed-action bomb.

A large black panel opens that chapter, and then small panels with a freehand-drawn border appear, at first only occasionally interrupted by panels with the bold, ruler-rimmed standard frame (Figure 1). Gradually, it becomes clear that the penciled panels relate shreds of memory, which flicker through Suzu’s feverish dreams: sewing sessions with the grandmother, the encounter with Rin, time spent with little Harumi. The bold panel frames—and with them the external reality—are gradually gaining the upper hand until the word “murderer” slips out of Keiko’s mouth. The following page features the two already mentioned vignettes of Suzu’s hand: first, the strongly contoured bandaged stump; second, the faintly outlined healthy hand (Figure 2).

This differentiation by line type is highly medium-specific (although not necessarily salient). Consequently, the animated movie expanded the big black panel at the beginning of chapter 33 to a whole sequence which, according to a handwritten note of the director in the storyboard, departs from cel animation in favor of “something like cine-calligraphy,” [26] i.e., the technique of direct engraving on filmstrips as developed by Norman McLaren with Blinkity Blink (1955). Accompanied by crackling noises, white lines flash. The voice of the grandmother can be heard and Suzu’s monologue. Then the ground changes from black to white. The cel-animated colored figure of Suzu runs down a coastal path, indicated in gray lines, until a look at the bay, drawn with crayons, opens and Harumi can be seen and heard. Sound compensates for what stayed invisible in the manga’s gutter.

Magazine Matters

Kouno conceived In This Corner of the World not as a book, but as a serial narrative, and published it in a magazine that appears to primarily target male readers judging from its cover photos and manga contents (seinen manga). [27] In the Japanese context, this raises the issue of gendered genre. Does the cute-looking protagonist cater to a generically masculine gaze? Are elements of generically feminine manga fed into a masculine domain? The very fact that all kinds of visual formats are appropriated by the artist’s, and through her Suzu’s, hand may suggest an inclination to reducing otherness in a shojo-mangaesque way. [28] Yet, significant formal characteristics of shojo manga are missing: The linework is mainly rendered with a G-pen, a device that has shaped the appearance of graphic narratives for young men (gekiga, seinen manga). In addition, screen tone is eluded as is the preference for printed script and more than two saliently alternating typefaces.

In contemporary manga, printed script predominates, for better readability as well as aesthetic transparency (that is, an access to characters and storyworld unimpeded by material concerns). Hand-lettering is by convention used for onomatopoeia and, in female genre tradition, extradiegetic, often funny comments on characters and situations. [29] Kouno, however, avoids such commitment to genre. Her manga leans on pictoriality rather than scripted text to evoke closeness, such as in the case of the drawing paper or the left-handedly drawn background. Her speech balloons are almost uniformly filled with printed characters. Handwritten onomatopoeiae are employed sparingly, until the manga’s last third: when the sirens no longer seem to stop, the panels become superimposed by sound words that assume a ropelike physicality.

Furthermore, the paneling does not necessarily suggest affiliation with the genre of shojo manga, which tends to foreground space, shifting the reader’s attention back and forth between panel and page. And even if the G-pen plays a crucial role, an affiliation with seinen manga—which foregrounds the flow of time through transition from panel to panel—is not suggested either, although Kouno apparently invites the reader to proceed from panel to panel and from tier to tier, slightly offsetting the vertical gutters. Only in parallel montages of concurrent action is the grid geometrically accurate. This becomes evident, for example, on one page towards the end of chapter 32: Suzu and Harumi are sitting in an air raid bunker. To distract her niece, Suzu draws the faces of the family members into the dusty ground. While a sequence of vertically arranged sound words visualizes both the force and the length of the bombing, the underlying panel grid suggests less a process than a stagnation of time: The gaze of the characters, and the reader, while guided from right to left, is urged by onomatopoeiae to turn downward, which enforces the oppressiveness of the situation.

Such attention to the still space of the printed page manifests further in the occasional material juxtaposition of image and script. When Suzu lies on the sickbed and cannot yet make out reality, a horizontal panel suddenly appears in the middle tier across the entire double-page spread (chapter 33). It repeats an originally vertical panel showing Suzu and Shusaku on a bridge and their reflection in the water (in chapter 15), which is now turned 45 degrees to the right. Compared to the panels on the upper and bottom tiers, the visible world appears reversed. The voices, however, remain in the medial “normality” as the speech balloons feature the Japanese dialogue in the usual vertical arrangement. Such a juxtaposition of seeing and reading direction can already be found in Kouno’s first Hiroshima manga, the twenty-nine-page story “Town of Evening Calm” (Yunagi no machi, 2003). [30] The protagonist, a young woman who feels guilty about having survived, suddenly runs up a vertical panel, away from the dead in the ground. But the Japanese lines of her monologue, which are to be read from top to bottom, pull back the reader’s gaze after each upward movement, thus anticipating her eventual fall over (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Material opposition of image and script in Kouno’s first Hiroshima manga Town of Evening Calm, in Kouno Fumiyo, Yunagi no machi, sakura no kuni (Tokyo: Futabasha, 2004), 24–25. © Fumiyo Kouno, Futabasha, 2004.

Considering the above, Kouno’s graphic narrative clearly defies conventional genre attributions, and it even uses the physicality of the manga magazine to set itself apart from the genre of that very magazine, in this case, seinen manga: The installments of the series were placed between the table of contents, actually occupying the last page, and the back endpaper (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5. Last page of chapter 32 upon first publication in magazine Manga Action, no. 13, 2008 (Futabasha). Bottom right margin: invitation to read also the next issue; left page: advertisement of a dating site, addressed to male readers. © Fumiyo Kouno, Futabasha 2008.

Figure 6. First page of chapter 33 upon first publication in magazine Manga Action, no. 14, 2008 (Futabasha). Right page: Table of Contents, with Kouno’s title on the bottom right (indicating page 311). Bottom left: Editor’s announcement that vol. 2 of the series will go on sale on July 11; left margin: “Suzu caught been between and reality.” © Fumiyo Kouno, Futabasha 2008.

While popular series appear far ahead in a manga magazine, In This Corner of the World slipped into the last corner, like a humorous extra, a “gag manga,” not to be taken too seriously. [31] The deliberately marginal positioning within the magazine began with chapter 2, when Suzu moved to Kure, a marginal “corner” of world history from the point of view of the atomic bombings. Seen from Kure, the atomic cloud of Hiroshima did not look like a mushroom, according to the image on the last page of chapter 37. But while this image suggests a peripheral, regionally specific view, manga critic Yoshimura Kazuma nationalizes it as Japanese in juxtaposion to the mushroom cloud as an icon established by American photographs. [32]

The material marginality of Suzu’s experience is lost in remediation when two pages, which were initially published with an intermission of two weeks, come to form a double-page spread in the book edition. Likewise lost, especially in translated editions, is the intricate interplay of the format of serialization with the diegetic time of action: The frontispiece of chapter 1 indicates “December 18,” which corresponds to the year Showa 18 (1943), but also Heisei 18 (2007), the release date of this manga chapter. In the apparently conservative reference to the imperial calendar, according to which, for example, the downfall of the Empire in 1945 does not necessarily appear to be a caesura (as the Showa era lasted from 1926 to 1989), the manga conjoins past and present yet again. Finally, it deserves mention how the dust jacket of the third Japanese volume anticipates unobtrusively the narrative’s tragic climax by showing Suzu lying on her back with her arms straight up, but her right hand folded inward (Figures 7 and 8). This is easily overlooked, for example, in gallery exhibitions that give preference to framed color illustrations over monochrome paneled pages.

Figure 7. Dust jacket of vol. 3 of the Japanese edition (Kouno, 2009), in the reader’s hand.

Figure 8. Dust jacket of vol. 3 of the Japanese edition (Kouno, 2009), unfolded. © Fumiyo Kouno, Futabasha 2009.

Conclusion

In This Corner of the World is an exercise in conjoining: the wartime past and the (in contemporary Japan) increasingly oblivious present, a politically charged history and the easily relatable personal act of drawing, haptic participation and critical contemplation. It accomplishes such conjoining through the deliberate employment of manga-specific materiality as grounded in the Japanese mediascape, so that parts of it may get lost in translation. With respect to the printed page as a site that conjoins multiple panels and as such different views, critic Nakamura Tadashi has highlighted the interplay of subjectivity and objectivity (or the imaginary and the symbolic) as characteristic of the manga medium in general and Kouno’s manga in particular. Neither privileging one of the poles nor fusing them beyond recognition, In This Corner of the World indeed keeps a balance, juxtaposing different types of line within the same page space, redrawing printed matter by hand, and detaching the hand from Suzu in terms of character ontology. Ultimately, Suzu is anything but able to escape the harsh social reality qua imagination. Manga as a highly affective popular media has been promoting a relation between subjectivity and objectivity that resembles sekai-kei — “characterized by the immediate link between micro-condition, the protagonist’s family and school (I), and macro-condition, concerning global crisis and ruin (world).” [33] In contradistinction, In This Corner of the World provides plentiful historical knowledge to the receptive, and margin-sensitive, reader.

But as indicated in this article’s introduction, manga’s medium specificity includes aesthetic form as much as sociocultural disposition. With regard to freehand drawing, the use of the pencil, and an emphasis on the sense of touch, the indifference towards genre, and furthermore its historical realism but lack of semantic straightforwardness, In This Corner of the World clearly deviates from what sells as “manga proper” in the domestic and global marketplace. At the same time, this graphic narrative cannot be denied distinctive manga features, ranging from magazine serialization and the centrality of a cute-looking character to the prioritization of closeness and affective participation over critical distance. Rather than presenting another, only this time Japanese, variant of “middlebrow” fiction located in between the modern dichotomy of high art and literature (or the “aesthetic disposition”), and industrial mass culture (or the “popular disposition”), Kouno’s conjoining coincides with the “imagination-oriented disposition” of recent fan cultures that entwine the specialized expertise of the first with the penchant for sharing of the latter. [34] A focus on forms in their materiality rather than representation may help to illuminate such “third” disposition across fields.

有趣的是,最初使我超脱“反战败”的所谓话语而对这一幕有更深了解的,并不是女性主义视角,反倒是丸山真男的《忠诚与反叛》(笑)

机翻:

结尾部分的长难句翻译可能还是不太清晰,之后再校对一下;有的时候,原作者随便扯一句就概述了其他人整篇论文的内容,所以不得不参考附录里的参考文献一起解读这种掉书袋的句子...我还没看第[34]条文献,这里偷懒了

disposition 批评术语,布迪厄使用过,没有太好的翻译,通常译为「倾向」。 https://book.douban.com/review/4192943/

pure aesthetic disposition和popular aesthetic disposition都是布迪厄术语。

imagination-oriented disposition就变成了「想象力导向的倾向」,非常别扭的叫法,没有想好怎么译。

penchant 译成「倾向」与「disposition」冲突,译为嗜好可能更好。

fan cultures 似乎是直译成「粉丝文化」,同人在英语里面应该是音译成「doujin」。 https://aims.cuhk.edu.hk/converi ... fun=&lang=en_GB

大段定语从句按照中文习惯还是拆分较好,重新翻译的话就是「河野的这种结合与粉丝文化的『 想象力导向的倾向』颇为相似,后者把审美倾向中的专业知识与大众倾向中的安利嗜好结合了。」这样子依然很拗口,因为对imagination-oriented disposition的理解依赖于第34条引文,而引文又依赖于对pure aesthetic disposition和popular aesthetic disposition的理解。所以搞文化研究的最终落点总是布迪厄。

https://www.academia.edu/3226585 ... Theory_with_errata_

FROM “GAME-LIFE REALISM” TO THE “IMAGINATION-ORIENTED AESTHETIC”: Reconsidering Bourdieu’s Contribution to Fan Studies in the Light of Japanese Manga and Otaku Theory

作者的话: